Genocide denial and spam

Low-effort Twitter spam networks have been a recurring form of propaganda related to Xinjiang and the Uyghur Genocide

Over the last several years, evidence of large-scale ongoing human rights abuses committed by the Chinese government against Uyghurs and other minority groups in Xinjiang has surfaced with increasing frequency. These abuses, which include mass detention, forced labor, parent/child separation, and forced sterilization, are commonly referred to as the Uyghur Genocide. Chinese officials have repeatedly denied that any of the reported abuses are taking place (even when presented with video), and a variety of social media campaigns have sprung up to echo those denials. On Twitter, this has often involved spam networks composed of similar-looking accounts tweeting identical tweets about Xinjiang.

Since late 2020, @ZellaQuixote and I have been tracking (some of) these spam networks. They aren’t hard to find — running a Twitter search for “Xinjiang” and looking for repeated tweets and unusual patterns in account creation dates will frequently reveal them. Twitter generally bans them sooner or later, but replacements quickly emerge.

A list of the Xinjiang-related spam networks we’ve studied, in more or less chronological order:

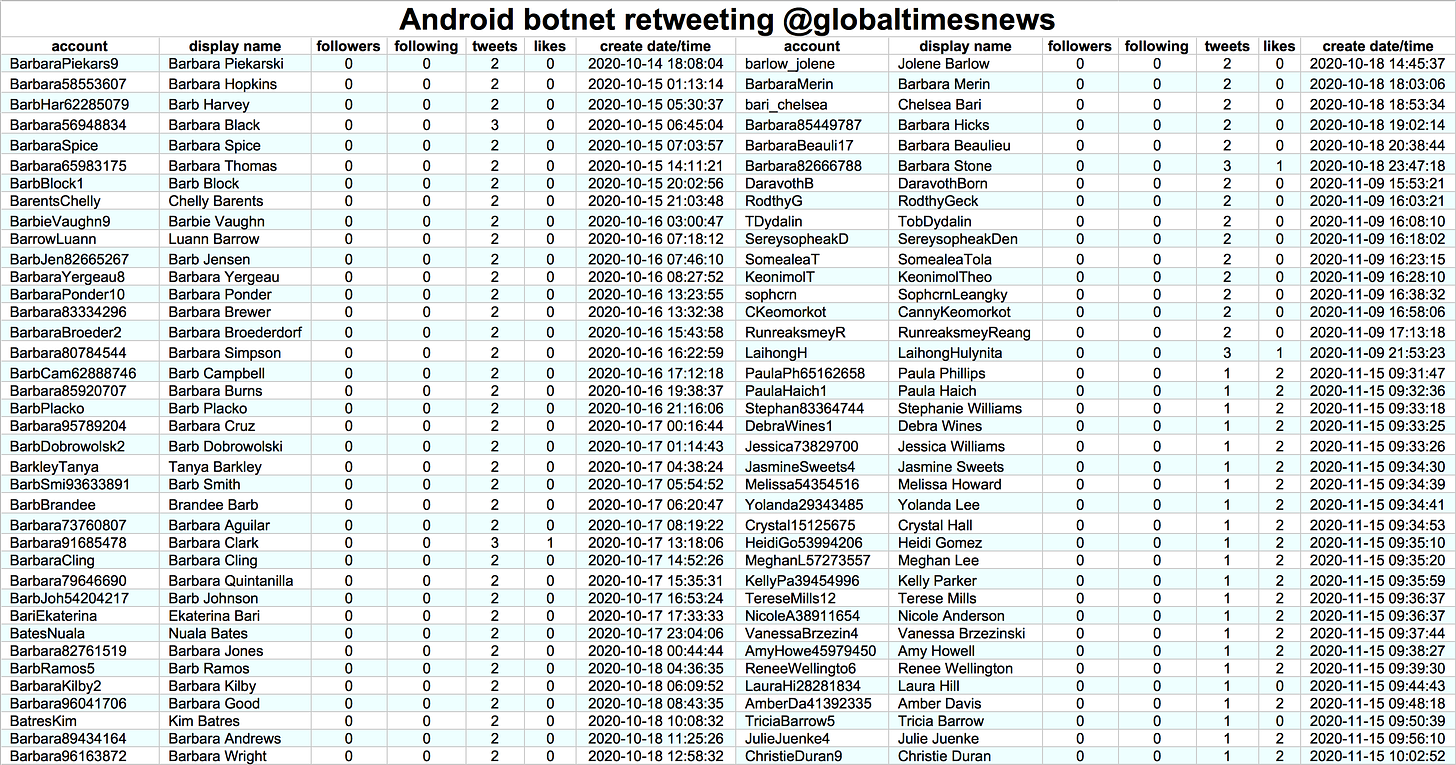

Two groups of inauthentic accounts (7258 accounts created in late 2019/early 2020 and 76 accounts created in late 2020) retweeting a Global Times article denying the existence of detention camps in Xinjiang

674 inauthentic accounts retweeting content about Xinjiang from Chinese government officials and state-affiliated media accounts in late 2020/early 2021

479 inauthentic accounts sharing a story about an arm reattachment surgery performed at a Xinjiang hospital in a variety of languages in May 2021

65 inauthentic accounts tweeting a video titled “Mother’s Day Greetings from Xinjiang” in May 2021

354 inauthentic accounts spamming links to videos about Xinjiang at journalists and bloggers in summer 2021 (Grayzone editor Max Blumenthal was a recurring favorite)

200 inauthentic accounts having identical “conversations” with each other about cotton production in Xinjiang in fall 2021

93 inauthentic accounts attacking the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, passed by both houses of the U.S. Congress in December 2021 and signed into law by President Joe Biden

152 inauthentic accounts posting Xinjiang-related propaganda during the 2022 Winter Olympics, frequently accompanied by Olympic hashtags

27 inauthentic accounts tweeting feel-good content about Xinjiang accompanied by the hashtags #genocide and #humanrights in early 2022

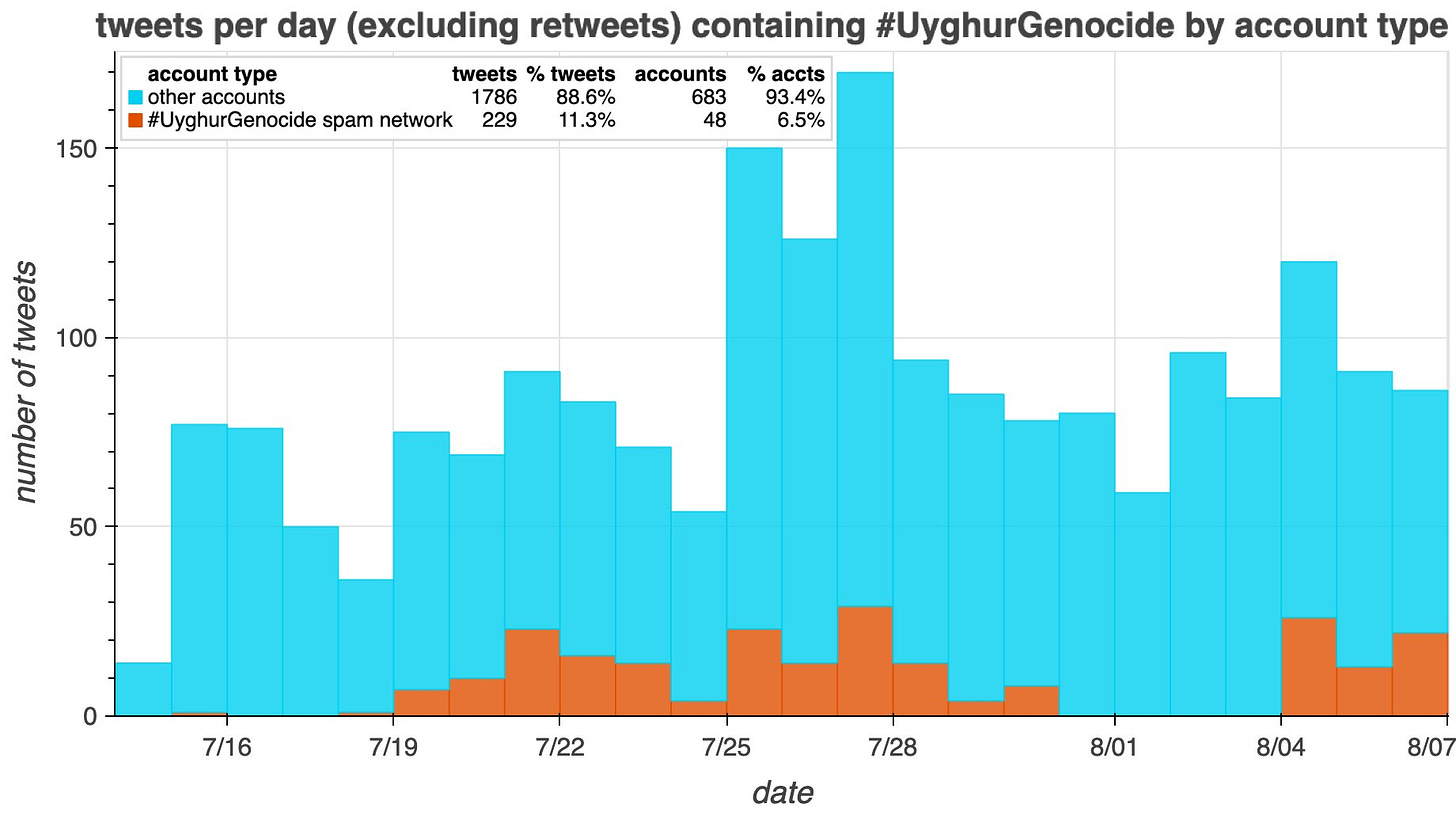

48 inauthentic accounts tweeting feel-good content about Xinjiang accompanied by the hashtag #UyghurGenocide in summer 2022

58 inauthentic accounts tweeting a mix of genocide denial and feel-good content about Xinjiang in summer 2022

48 inauthentic accounts attacking an August 2022 United Nations report documenting human rights abuses perpetrated against the Uyghur population in Xinjiang

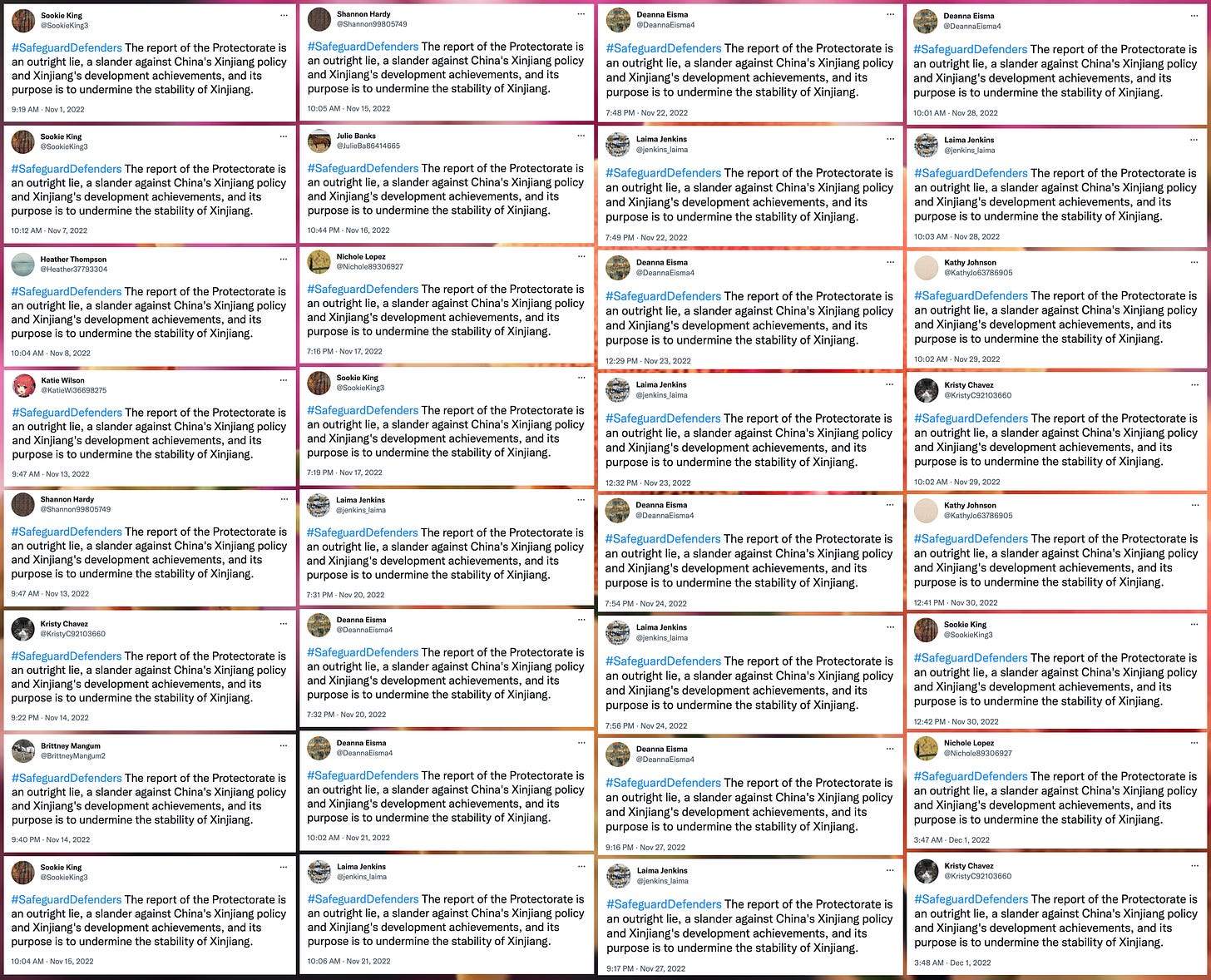

25 inauthentic accounts attacking the nonprofit group Safeguard Defenders, which has issued reports on a variety of human rights abuses in China

6 inauthentic accounts with GAN-generated faces tweeting a mix of genocide denial and feel-good content about Xinjiang in summer 2023

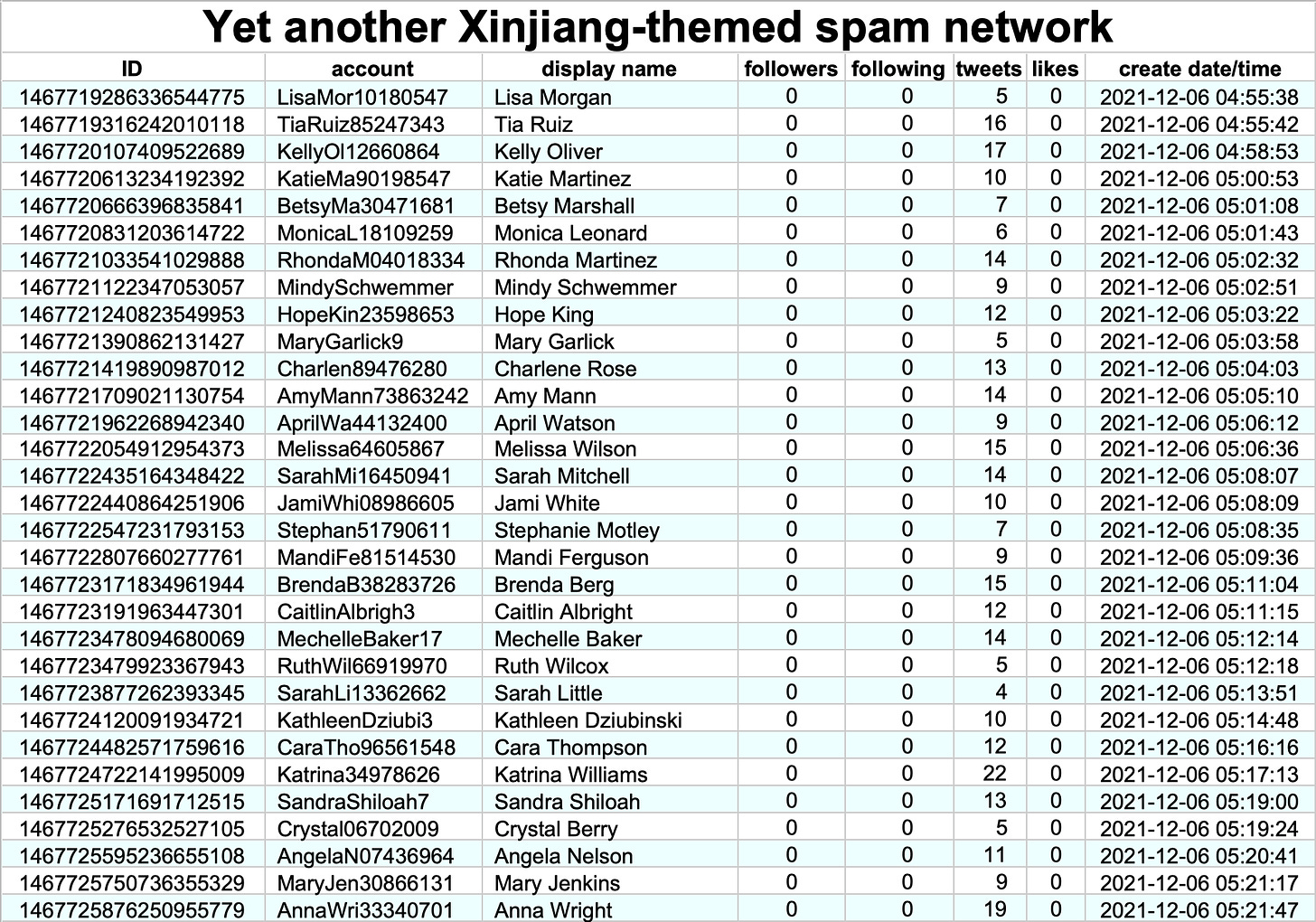

These spam networks generally consist of batches of similarly-named accounts created within a narrow time or date range. Many of these networks use random traditionally female English first names combined with random last names. (Sometimes the randomization apparently gets skipped, as with the network where 36 of the 76 accounts were named “Barbara”.) The accounts in these networks frequently have few or no followers, follow few or no accounts, and have similar numbers of tweets.

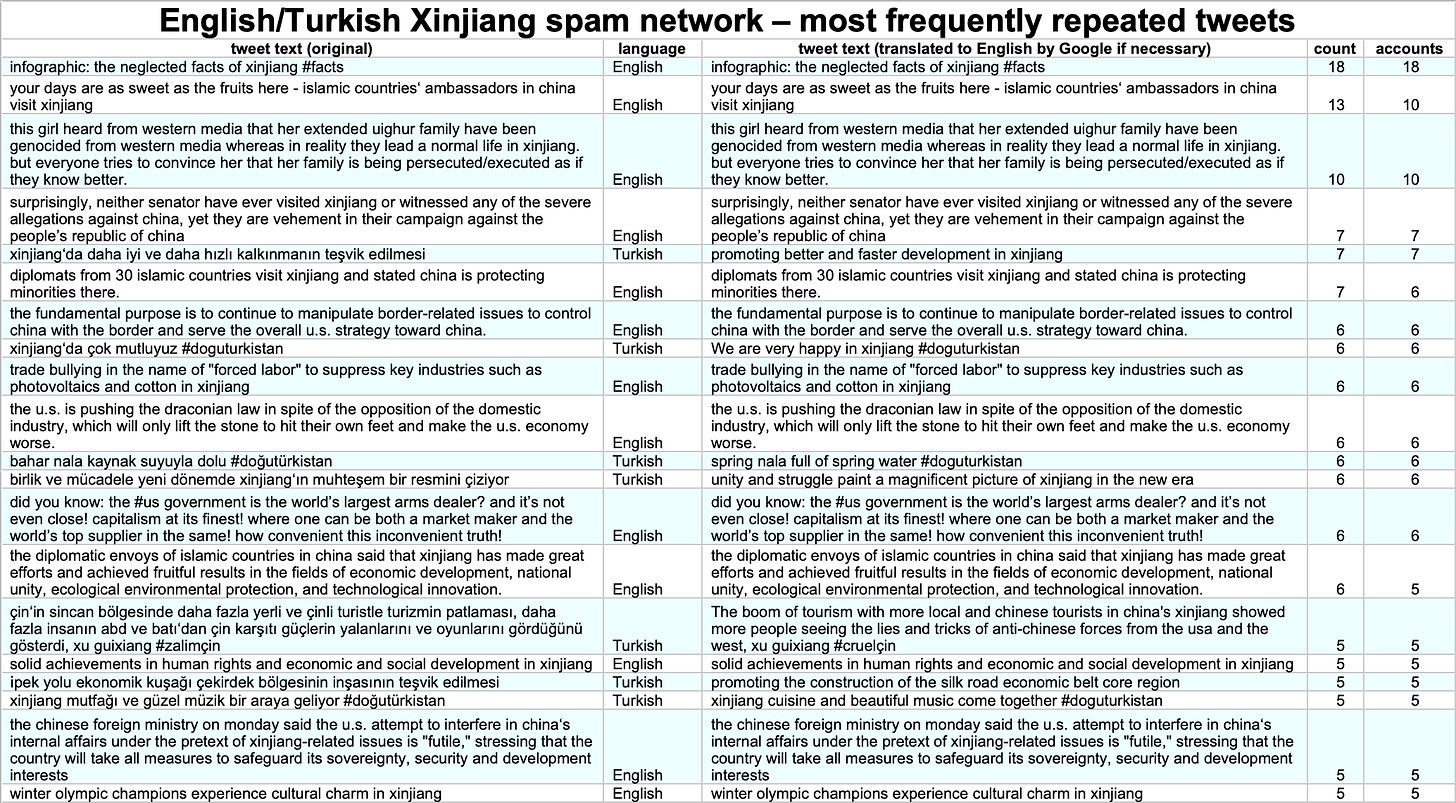

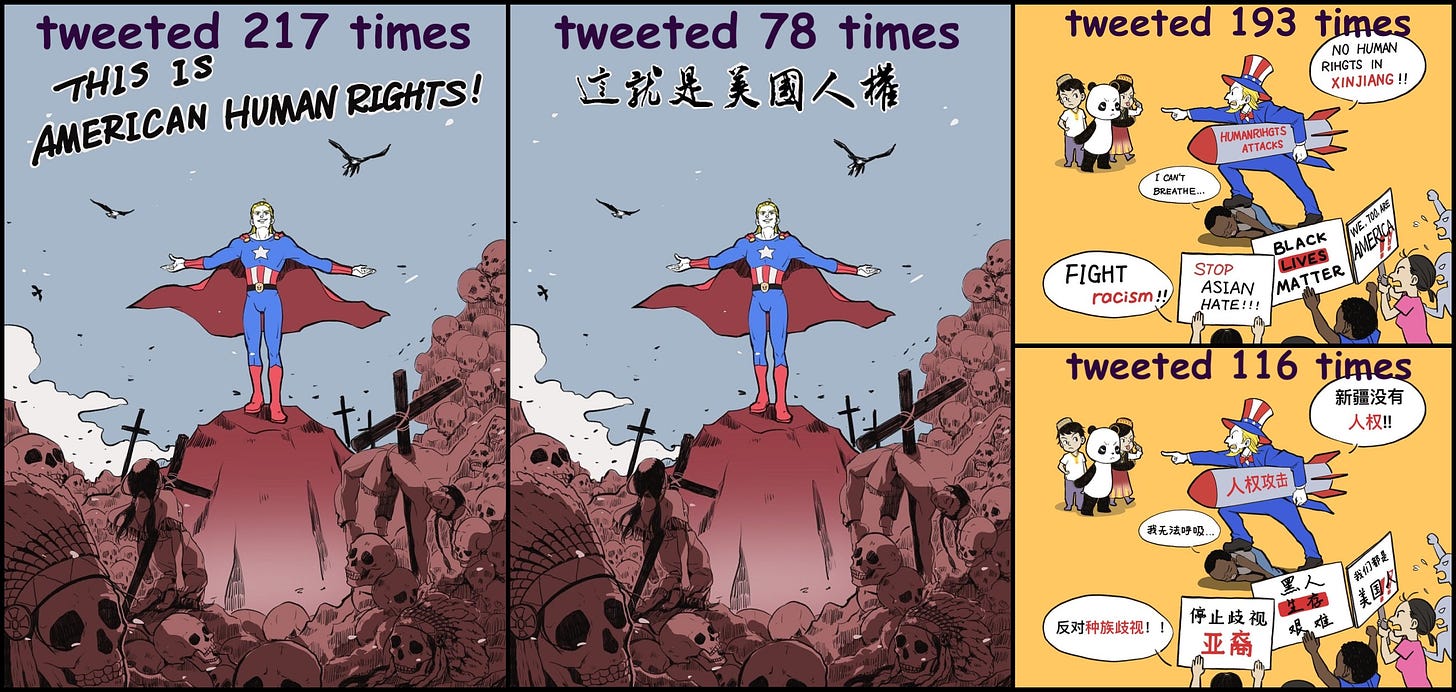

The content tweeted by these spam networks is extremely repetitive, with the same text tweeted verbatim by multiple accounts (and sometimes multiple times by each account). Some of the networks tweet duplicate images and video clips as well, and some tweet in multiple languages. The content they tweet falls into a few major categories:

Overt denials that the Chinese government is committing or has committed human rights violations against the Uyghur population in Xinjiang

Framing Western criticism of China’s human rights record as hypocritical due to crimes committed by Western nations (also known as whataboutism or whataboutery)

Feel-good content about Xinjiang, such as pretty pictures, fun videos, and positive economic news

Some of these networks attempt to create the illusion of authenticity by having “conversations” wherein the accounts in the network reply to each other’s tweets. As with the other content from these networks, their discussions are repetitive, usually consisting of one set of accounts tweeting identical tweets and another set replying with identical replies. When viewed individually, these might at first glance look like genuine brief interactions, but they’re just one more form of spam.

Does this type of low-effort spam actually accomplish anything? Although the accounts in these networks generally don’t get many (or any) followers and therefore have very little individual reach, they do sometimes collectively manage to inject noise into searches for various words and hashtags related to Xinjiang and human rights abuses there (including the word “Xinjiang” itself). For example, roughly one in every nine tweets containing the #UyghurGenocide hashtag tweeted between July 14th and August 6th, 2022 was a tweet from one specific spam network. All of these spam tweets were feel-good tweets about Xinjiang (mostly duplicate photos and videos) rather than content related to the Uyghur Genocide, diluting the intended purpose of the hashtag.

Note: this article may be updated if the techniques used by these networks evolve significantly in the future.)